My Black mama

Art by Dickson Nedia Were

In my Kenyan community, there is a beloved song, its melody woven through generations, that goes like this:

"Mama nu mulayi koo, mama

Mama nu mulayi mama

Khali makhono kamwame, mama

Mama numulayi koo mama …”

The song’s message is simple, yet profound: Mama is the best—no matter what. Even if her hands are dirty from life’s work, she remains the very best.

My mother would sing this song to me whenever I challenged her as a rebellious teenager, or when I insisted that other mothers were better than she was.

When my son Christian was about five, we went to a supermarket. I was the only Black woman in the store, surrounded by white mothers and their children. As kids do, Christian wandered off, exploring on his own. Suddenly, realizing he’d lost sight of me, he called out, “Mama!” One of the white women, thinking it was her child, replied, “Yes?”

Christian looked at her and replied, “Not you. My Black mama…”

“Black mama… Black mama…” he began to shout, his voice echoing through the shop. Laughter bubbled around us, but for me, it was a profound moment. My mother’s song came rushing back into my memory.

"Mama nu mulayi koo, mama

Mama nu mulayi mama

Khali makhono kamwame, mama

Mama numulayi koo mama …”

I remembered, too, once, when I was ten, at boarding school: a friend of mine refused to go to her mother when her mother came to school barefoot. That incident has never left me, and whenever I think of this girl, I remember that scene. How could she? Why did she do that? Were questions that went unanswered.

In one of the Zoom meetings, a professor from Canada confessed to doing the same and having been traumatised with guilt and shame for the rest of her life, and she wrote a book dedicating it to her mother, who joined her ancestors years ago.

There I was, my son proclaiming with pride, “I want my Black mama.” I cherish that moment to this day; I have never been prouder. Yet I can’t help but wonder how those mothers felt when their children were ashamed of them.

We cannot underestimate the power women hold—as sisters, mothers, daughters, and wives. For those familiar with the Bible: Miriam, at the river, offered to find a maiden to care for baby Moses—here, a sister saves a life. At the wedding in Cana, Mary simply told her son Jesus, “They have no wine,” and with that quiet nudge, a miracle flowed—there is the silent power of a mother. When Herod’s daughter danced for him, he promised her anything; she turned to her mother, who answered, “Ask for the head of John the Baptist.”—We witness the influence of a daughter. At Jesus’ crucifixion, Pilate’s wife sent a warning not to harm Jesus, and Pilate washed his hands of the matter—here stands the power of a wife. In each story, we see women of influence making choices—between compassion and cruelty, between justice and injustice.

Women have fought differently.

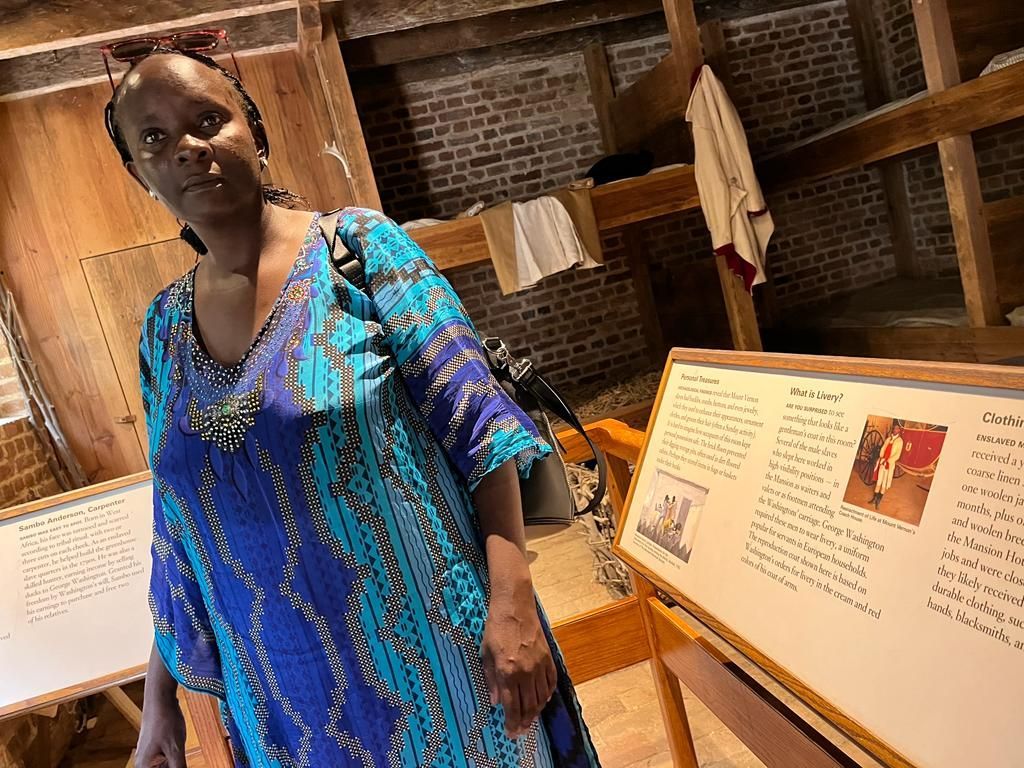

Slavery has cast a long, painful shadow over generations. Yet the anguish of African women—whose husbands and children were ripped away, leaving them frail, heartbroken, and alone—too often goes undocumented. Still, these women found the strength to keep life moving forward. That is why you, woman of African descent, and I are here. We honor you, Mama Africa.

There are countless women like Winnie Mandela, who sacrificed for their country’s freedom. Despite her flaws, she is worthy of the highest honor. Josina Machel of Mozambique fought tirelessly for women’s right to join the liberation struggle, from bearing arms to political action. In Nigeria, Ransome-Kuti wielded her privilege to organize resistance against colonialism. Bibi Titi Mohammed in Tanzania mobilized women, spread information, and galvanized political action through cultural and economic networks. Their voices must never be silenced. In Ghana, Mabel Dove-Danquah—hailed as a trailblazing feminist—was ahead of her time, boldly advocating for women’s equality. She became the first African woman elected to parliament by popular vote.

In Kenya, Muthoni Kirima first took the Mau Mau oath in 1952. From then on, she had to balance her role in the revolution with her family responsibilities. She began by using her trading connections to gather information about events unfolding among the Mau Mau in the forest. She also organized the oaths of other people. Wangari Mathai, who fought for the environment, and so many other women from South, North, West, and East Africa.

In America, we know of Rosa Parks, Toni Morisson with her books, Maya Angelou with her teachings, and Coretta King. Women in both leadership and supportive roles.

As women of African descent, we must carry forward the lessons and courage of these foremothers.

Today, women of African descent still quietly bear the pain of losing husbands and children—echoes of the suffering endured in the days of slavery.

On 25 May 2020, the world witnessed the pain of every Black woman in broad daylight. On camera.

“Mama… Mama…” Those were George Floyd’s final words. They shattered the heart of every Black mother. Any Black mama with a son wept that day—I have two sons, and I cried for days in silence, keeping myself busy just to avoid the haunting flashbacks on TV. Even now, I search for answers in quiet moments, struggling to comprehend the depths of human cruelty.

We all watched. Our children watched—Black and white alike. We may never fully grasp the true impact of that day, but one thing is certain: we witnessed a man fall from grace.

Women are the anchors of life.

Lonnae O’Neal is a senior writer at The Undefeated, and she expressed the meaning of that word mama at the moment of dying. She wrote:

Floyd called for her mama as a memory's assurance. A call to your mother is a prayer to be seen. Floyd’s mother died two years ago, but he used her as a sacred invocation. He is a human being!” comes an anguished plea from someone in a desperate attempt to engage the officers’ reason or compassion, or oaths of office. But in that moment, those officers are beyond the reach of humanity. Not Floyd’s, but their own.

She goes on to write…

I didn’t want to click on the video. I didn’t want to see another police snuff film. I didn’t want to watch whatever it is that compels someone to put his knee into a man’s neck until he can no longer draw breath. But I heard this black man had called out to his mama as he lay dying, and I, too, am a black mother. One of the ones, since time immemorial, who have to answer the sacred call. Who has to answer the call for the divine sisterhood of black mothers? Even when they are not our own, we are asked to bear witness.

I was in the delivery room with my son, in pain with no medication, save the one that magnified my contractions. As my vision narrowed, I focused on a point above me, and I heard the nurses talking about me as if I wasn’t there. I stared at the ceiling, and over and over, I called out for my mother.

There are moments when it feels like life hangs in the balance, and in those moments, we want to go back to the beginning, when we were known.

Dying soldiers called out for their mothers, according to Civil War battlefield reports. Last year, an article from The Atlantic cited a hospice nurse. “Almost everyone is calling for ‘Mommy’ or ‘Mama’ with the last breath.”

We are the ballast. The anchors. A way for those who are close to the edge to find their way back, or their way home. This is true for black mothers, who are especially tested and learned in all the dread fates of black bodies. We are the hedge against the people who don’t see us. We are an assertion of black life.

For black people who feel they are about to be taken from themselves, we are the assurance of memory….

To conclude, I would like to quote Mama Madikizela-Mandela.

“As a woman, it is a personal, individual choice you make to make a difference. To understand that my neighbour is not as privileged as I am. To extend your heart to your neighbour and make a difference in her life… that is the democracy you should protect.

"Mama nu mulayi koo, mama

Mama nu mulayi mama

Khali makhono kamwame, mama

Mama numulayi koo mama …”